Dow CEO on Plastics Treaty: Governments Must Mandate Recycling

Plastic pollution has hit a crescendo.

In Ottawa, Canada this week, the United Nations will reveal staggering plastic waste numbers showing the lows of humanity, flagrantly tossing plastic into marine environments that torture and kill sea life, contaminating water supplies that in turn irreparably harm human health.

The Canadian government is hosting nearly 200 countries, global nongovernmental organizations and corporations for the fourth session of the UN Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-4) April 23-29.

They will work to advance the world’s first plastics treaty, expected to be finalized this fall in Korea and codified in January 2025. That meeting could be in Ecuador, Peru, Rwanda, or Senegal.

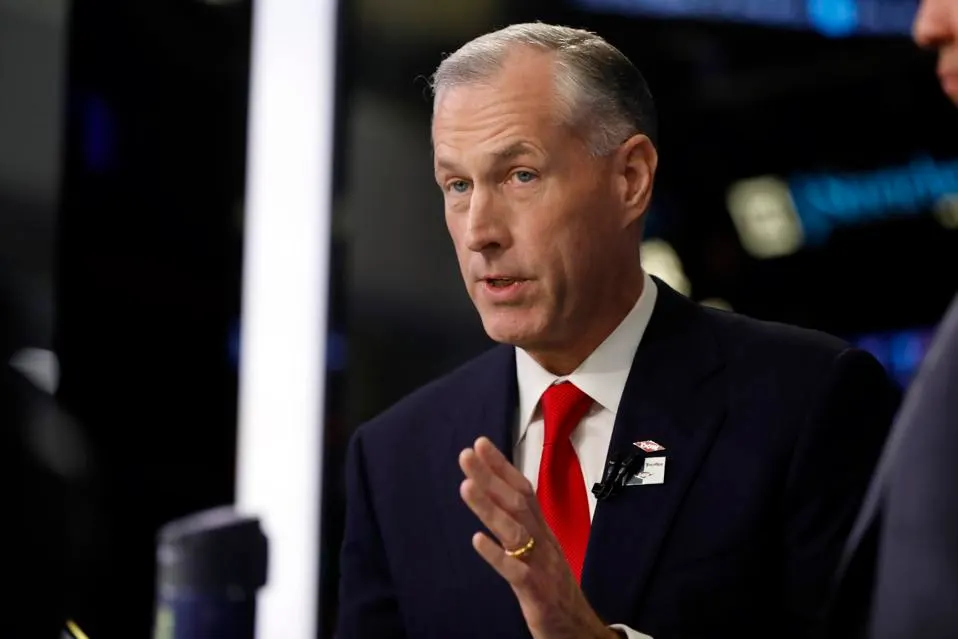

Jim Fitterling, chairman and CEO of the world’s largest plastics producer, shared a message with me: Governments must mandate recycling and provide more access to waste management.

Fitterling, who has been at Dow’s helm since 2018, says he wants to see the world shift from a linear economy, where humans dispose of items after one use, to a global circular one, something even Benjamin Braddock from The Graduate might be into.

Dow’s plan is based on recycling mandates, expanding alternatives to traditional oil and gas feedstock to create plastics, blending virgin plastic—newly manufactured plastic—with recycled materials, and reducing emissions from plastics manufacturing.

Fitterling believes all feedstocks and technologies are needed, as well as collective action where policy drives investment and change, and every global citizen do their part.

But it’s strong brands and government targets that will catalyze the change.

“If I go back a decade or more, we were starting to focus on this area, and there wasn’t a strong demand at the brand owner level to take the recycled content,” Fitterling said.

Now nearly 100 brands have signed onto the U.S. Plastics Pact, an agreement with a roadmap to achieve four key goals by 2025: define a list of problematic or unnecessary packaging and eliminate those products; make 100% of plastic packaging reusable, recyclable or compostable; recycle or compost 50% of plastic packaging; and use an average of 30% recycled content or bio-based content in plastic packaging.

“If you look at our production today, we have a target to grow 3 million metric tons a year of recycled materials on top of the products we make from virgin materials. It’s a new line of growth for us,” Fitterling said. “This demand from brand owners to have 30% of their materials be post-consumer recycle, that’s a huge change.”

The transition to a circular economy is “a big change” that “sounds easy, but isn’t,” Fitterling said.

“If you recycle a material, customers want to get the same performance, the same quality, of course they want it to be high quality.”

Outrage And Demand

“There are people that say it’s going to be the end of the plastics era,” Fitterling said.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

“Plastics continues to grow well above GDP levels and has for decades,” he said.

That’s demand.

The American Chemistry Council outlines a spectrum of critical industries that rely on plastics from healthcare to transportation, food preservation and service to space exploration and beyond.

During the brunt of the Covid-19 pandemic, plastics were critical components of personal protective equipment. When addressing food shortages from climate disasters, bottled water and plastic-wrapped food supplies are essential, according to ACC.

Cost plus fungibility drives plastic demand, Fitterling said.

In 2023, the global plastics market totaled $712 billion dollars according to Statista; it’s expected to grow to more than a $1 trillion market by 2033.

“It’s easy to use. It’s a material you can do a lot with from a product standpoint. There’s a lot of conveniences to it. There’s a lot economically to it. None of those things go away,” Fitterling said.

There’s a growing demand for plastic concurrent with global outrage over plastic waste.

The eco-friendly, biodegradable plastics market has grown. Its expected value will be more than $20 billion by 2026, rising from just over $5 billion in 2022.

At the UN meeting, Dow will show examples of recycling and products it makes from recycled materials, including materials made from biofuels.

“We have access to tremendous capabilities. We know the technology. We’re on the ground in many of these countries,” Fitterling said.

Dow manufactures in more than three dozen countries and sells plastic in more than 100.

Not Your Mother’s Tupperware

In 2019, Fitterling led Dow to become a founding member of the Alliance To End Plastic Waste, which drives circularity projects.

He endorses a new digital watermarking technology that developed countries, including the United States, could adopt. “When you get a package, there’s a watermark in it that may not be visible to the naked eye, but an optical sorter can pick it up in an advanced recycling facility and separate it out, so you get a higher quality raw material,” he said.

“We work the whole value chain from end to end. It’s important for us to bring together that knowledge to bear as we’re putting together policies on how to increase the amount of recycle, and how to do this in a scaled-up fashion,” to have higher impact but in a way that protects the environment, Fitterling said.

Dow signed a deal last year with Lancaster, PA-based New Energy Blue, to convert corn stover, the leftover parts of corn plants after harvest, into second-generation ethanol and clean lignin. Nearly half of the ethanol will be converted into bio-based ethylene feedstock for Dow plastic products. New Energy Blue designs, builds, owns, and operates biomass refineries that convert agricultural residues into low-carbon fuels, chemicals, and plastics.

“In Europe we have a partnership taking waste material from forestry—oils and other unusable byproducts—and convert that into plastics. There are many of those kinds of examples,” Fitterling said.

From 2001 to 2005, Dow had a joint venture with Cargill to make biopolymers from corn. Cargill bought Dow’s share in the venture and renamed the company NatureWorks PLA.

At the moment, the U.N. is suggesting an idea to replace laundry detergent in giant plastic jugs with a small dissolvable tablet, sans packaging.

“I think you’re going to see consumer demand for those kinds of things as well. The treaty will be open to all forms of that,” Fitterling said. “Innovation is critical. In the treaty you don’t want to say no to anything.”

Fitterling, leaning into the familiar “reduce, reuse, recycle,” mantra, said “Plastics have allowed the packaging industry to make strong, small, lightweight packages. That’s a waste reduction.”

“That’s important when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions,” Fitterling said. “If you’re shipping plastic packages versus glass or metal or some other alternative, you really have tremendous greenhouse gas” emissions reduction.

“It makes plastic the lowest CO2 per pound of product footprint that’s out there. That’s important,” Fitterling said.

Reuse influences design. “You have to make products that are designed to be recycled. That means polymers are collected easily…either at a store or your home or some collection point,” Fitterling said.

“You have to look at a range of policies that is going to drive that kind of outcome, making all forms of plastic able to be collected at curbside, having the ability to sort those out in high quality waste streams, and then having the consumer demand,” Fitterling said.

Recycling capability varies from region to region, and state to state.

AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

“If you go to Japan, they’re very advanced. More than 90% of plastic waste is collected and recycled,” Fitterling said. In Europe in general, reduction and recycle rates are well over 40%, he said. Consumers sort trash and recyclable material at home.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. recycles about 32% of waste. Only 9% of virgin plastic is recycled.

In the U.S. recycling is low for a couple different reasons, Fitterling said. “Many plastics are not collected at curbside. It’s not convenient for a customer to recycle plastics. Certain plastics are collected. Certain plastics are not.”

Because it’s not recycled in high volumes, plastic accounts for 18% of landfill trash in the U.S.

“Plastics don’t do anything in a landfill,” Fitterling said. It doesn’t harm the environment.

However, landfill owners could recycle landfill products to produce biogas or recycle plastic to generate natural gas to fuel landfill waste trucks.

UCG/UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP VIA GETTY IMAGES

“We estimated there’s $80-120 billion a year of raw material there that can come back and fuel new uses and new life for plastics. We think that’s worth going after and trying to get that back in,” Fitterling said. “If we didn’t do that, we would take more virgin feedstock and make more virgin plastic.”

In a circular economy, virgin plastic works together with recycled plastic.

“As you recycle, you need to compound with virgin materials to keep strength and functionality and so they go hand in hand,” Fitterling said.

Treaty Issues At Issue

One of the issues UN delegates will confront in Ottawa is whether certain recycling systems should be in the treaty.

COPYRIGHT 2023 THE ASSOCIATED PRESS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For example, Enhanced Producer Responsibility policies require producers to assess the environmental impact of their product. Such schemes could also shift financial responsibilities of recycling to a producer, away from municipalities, or they could provide incentives to producers for factoring in environmental impact when developing products.

Delegates in Ottawa will also consider national recycling targets.

Dow endorses both.

“Whether you’re talking about climate or whether you’re talking about plastics, the focus is on emissions and waste. It’s about waste reduction and being more efficient. It’s about making products with less emissions,” Fitterling said.

Dow is building the first net-zero hydrogen-powered plastic facility in the world, in Alberta, Canada, which is set to begin operations in 2027.

“So we’ll be able to make virgin plastics with zero CO2 emissions. That’s huge. If you can do that and you can recycle a material’s end of life, there’s no other packaging material that can come close to that kind of environmental footprint and that kind of life cycle analysis,” Fitterling said.

“That’ll reduce a million tons a year of CO2 emissions,” Fitterling said.

“Hydrogen is a byproduct off the production of the plastics so when we make ethylene, we make hydrogen and methane off the backend of the plant and we convert that through an autothermal reformer to pure hydrogen. It’s self-contained, a closed loop. Make ethylene, take the byproduct, convert it to pure hydrogen, and that fires the furnaces. It’s a pretty elegant design,” Fitterling said.